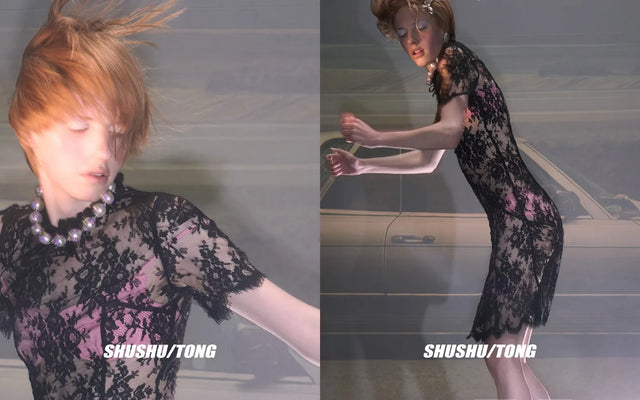

Brand spotlight

MASONPRINCE 麦森王子

Shenzhen , est. 2014

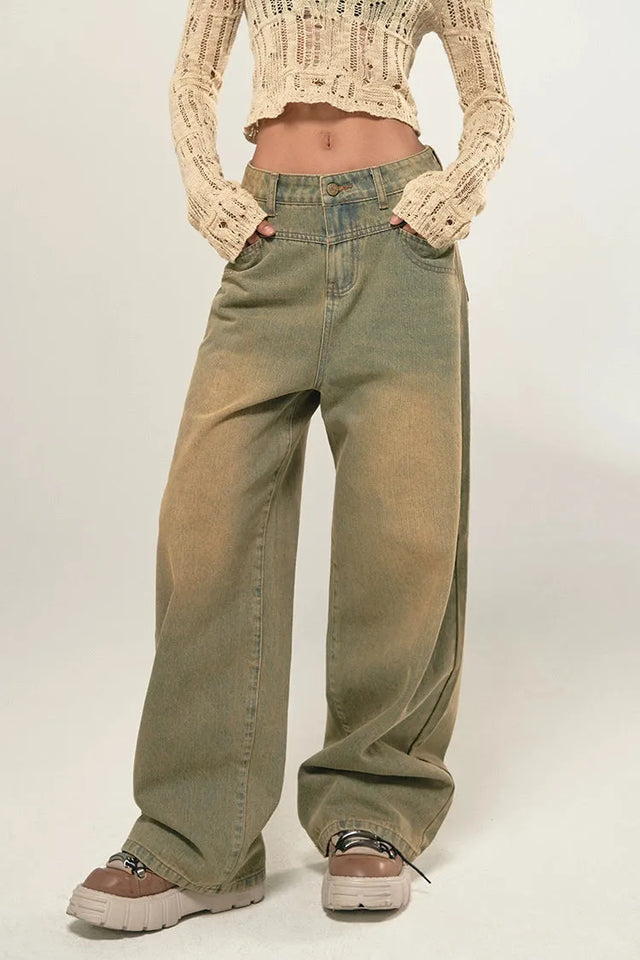

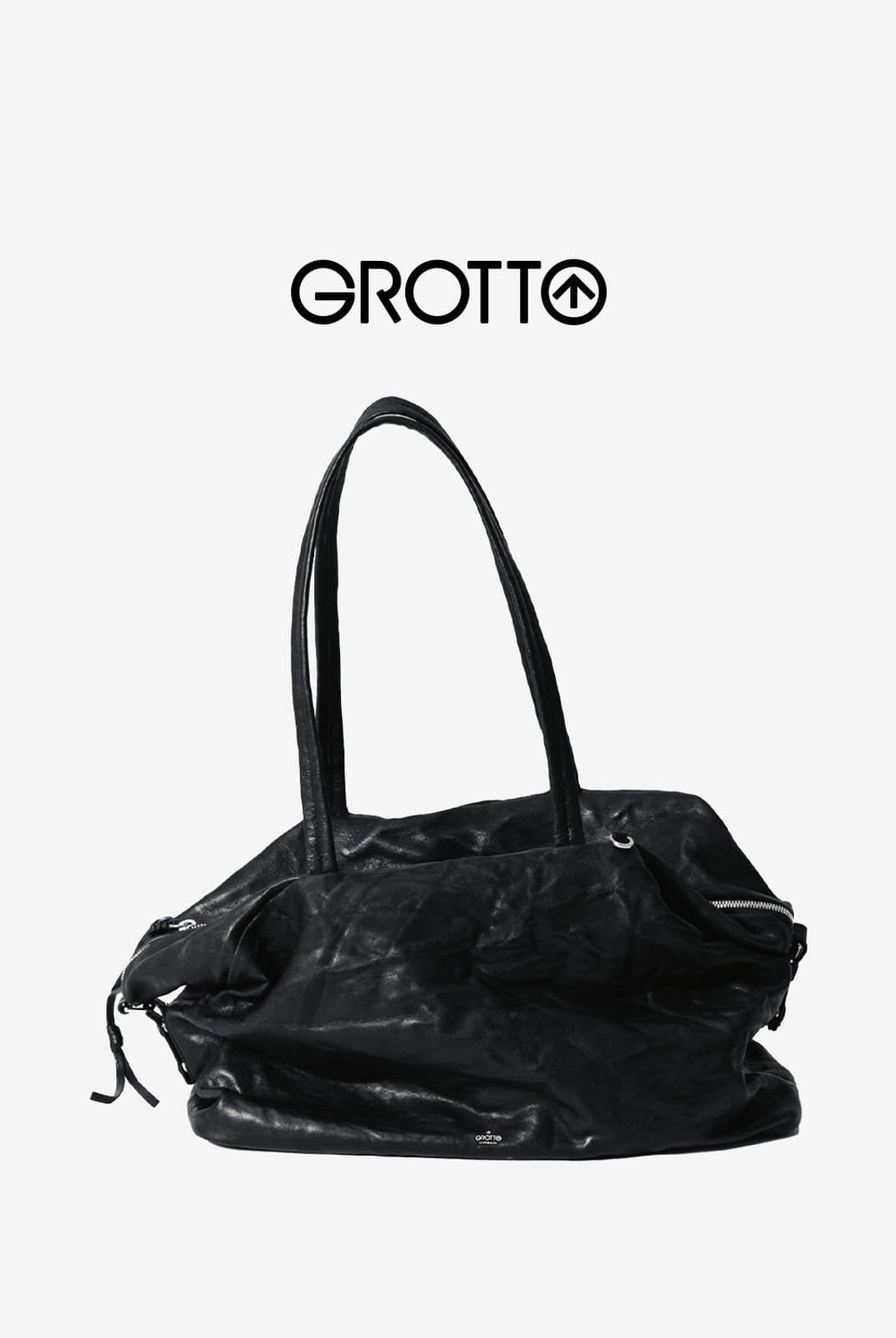

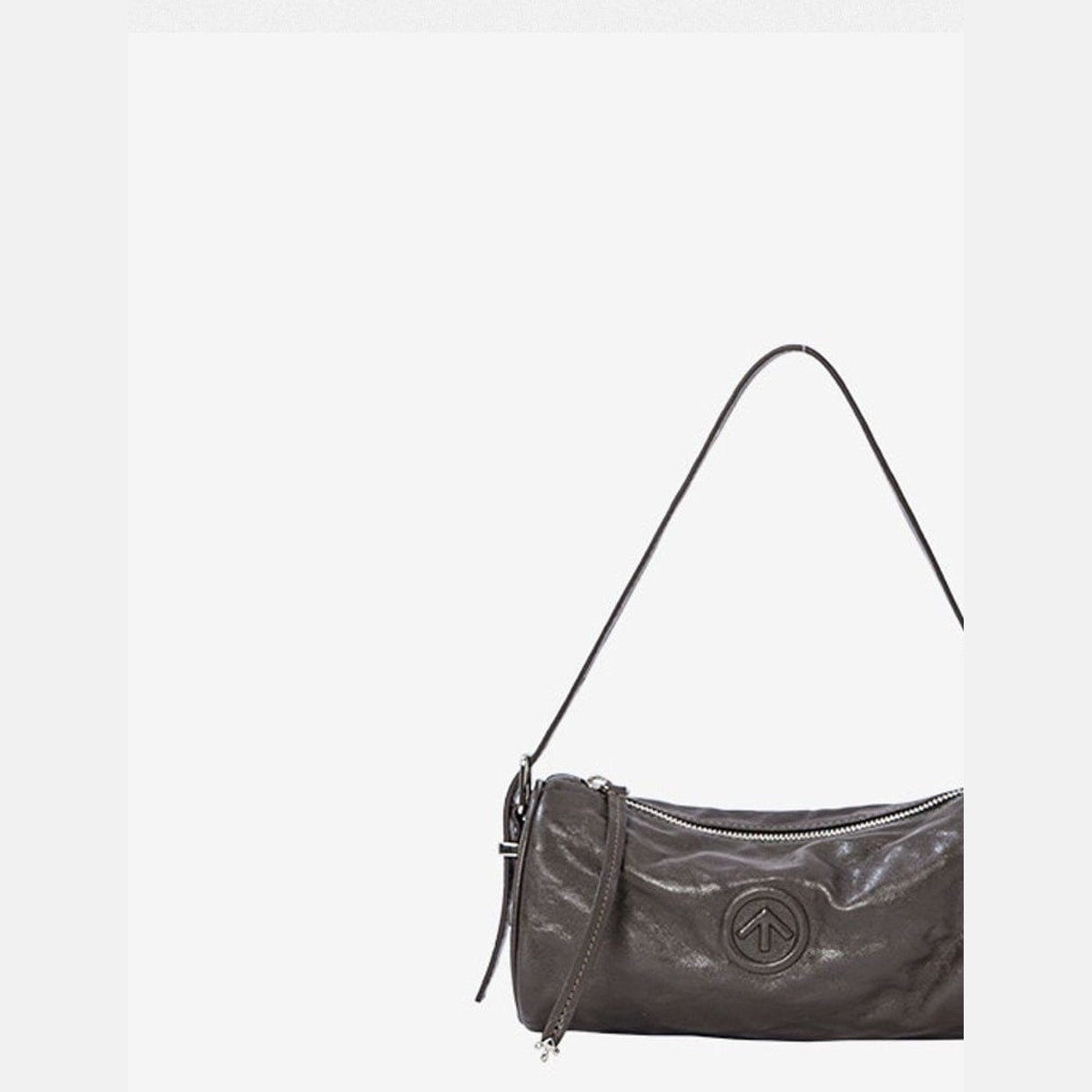

A decade of defying categorization. Founded by siblings Qiusen, Qiumu, and Qiulin Zhou, MASONPRINCE built a "classless fashion collective" — rejecting the cycle where youth culture gets absorbed into mainstream commerce. Their aesthetic lives in the tension between vintage and future, military utility and surrealist fantasy.